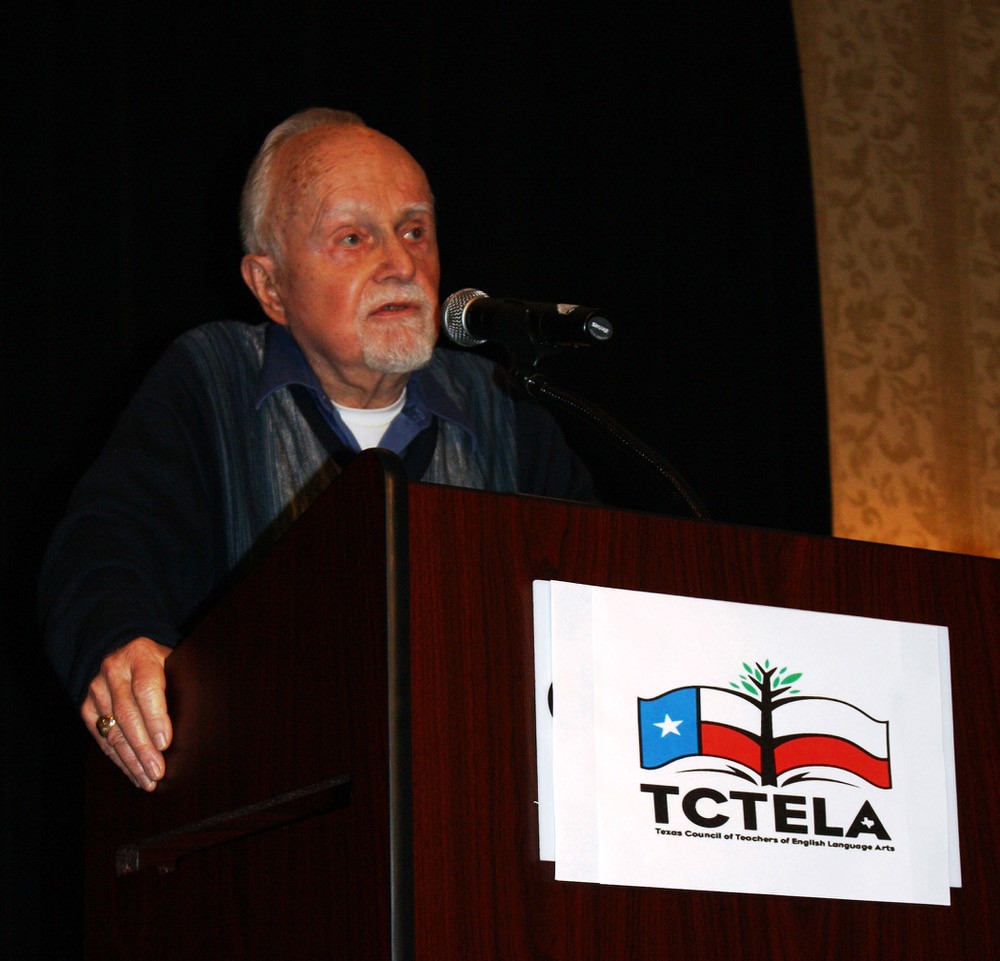

This post was written by NCTE Past President Kylene Beers. Photo was provided by members of the Texas Council of Teachers of English Language Arts (TCTELA).

Edmund J. Farrell died on January 14, 2024, at age 96. The author of well over 100 articles and monographs and many books and literature anthologies, Ed Farrell was a champion and visionary of English language arts.

He began his career as a high school English teacher and soon became department chair. After earning his PhD, he was the Supervisor of English Language Arts at the University of California, Berkeley. Next, he served as the Associate Executive Director of NCTE, where he worked with James Squire and helped move the Council forward.

Then, in 1978, he accepted a tenured appointment at the University of Texas in the College of Education. He remained there until 1992, when he retired as professor emeritus.

During his career, he was elected president of both the California Association of Teachers of English and the Texas Council of Teachers of English Language Arts. He was honored by NCTE with the Distinguished Service Award and the James R. Squire Award for extraordinary contributions to English language arts and by TCTELA with the distinguished service award that now carries his name.

And, he was my teacher.

I was a senior at the University of Texas enrolled in three classes and looking forward to student teaching, then a 12-week experience that included six weeks of observing the supervising classroom teacher and six weeks of teaching one class. I am quite sure that I chose the classes I would take that semester based on the times they were taught. I promise I did not know who my three professors, James Kinneavy, Maxine Hairston, and Edmund J. Farrell, were in the world of rhetoric, composition, and English education, respectively. That the three were friends, that each had strong connections to NCTE (particularly the Conference on College Composition and Communication), that they gathered with one another on Friday nights to talk about what their students had done (and not done) during the week was something I discovered much later. For that semester I only knew I was scrambling to keep up in Dr. Kinneavy’s class and was frustrated by Dr. Hairston’s ongoing admonitions to “Revise! Always revise!” Plus, I was quite sure that Dr. Farrell’s course requirements were too demanding and probably against some rule recorded somewhere.

When Dr. Farrell arrived at the University of Texas, one of his conditions was that he could direct 10 students who wanted to be secondary English teachers. He required that we would student teach for the entire semester, not six weeks, and that we would teach the morning or afternoon block, not one class. Additionally, he would observe us several times each week, and we would be expected to gather at his home at 4:00 p.m. each day for an hour. Then, once a week, we would return to campus for our 5:30–8:30 English methods class. Ten of us had registered for the class. Four students dropped as he explained the requirements.

We began. The six of us spread between two schools stumbled our way through the classes we were assigned to teach. Almost daily, Dr. Farrell would show up, sit at the back of the class, take copious notes, and then meet with us individually for a few minutes after a class. I remember sitting with him in the courtyard of Murchison Junior High in Austin, Texas, wondering what he meant as he asked, “Why did you choose to share Rikki Tikki Tavi with these students?” My answer that it was the next story in the Ginn literature book did not seem to be appropriate. “You must always know why you are doing what you are doing, and if the why doesn’t include how it helps your students, then you must ask why again.” I hear his words echoing in my mind so often these days.

After the school day ended, the six of us would arrive at his home to be greeted by Sean and Kevin, his two then-young sons, and his brilliant and oh-so-kind wife, Jo Anne. We would enter this home excited to share our newest adventures in teaching. His home was filled with the loud noises of two boys playing and the aroma of something just baked coming from the kitchen and thousands and thousands of books. He would usher us past the books that filled every hallway, that decorated the study, living room, and den, that sat upon coffee tables and end tables and the dining room table, to the kitchen where Jo Anne would have just removed fresh sourdough bread or chocolate chip cookies from the oven. With plates piled high and hands clutching tall glasses of cold milk, we would move to his study where he would pick up a worn copy of The House at Pooh Corner by A. A. Milne and begin reading aloud to us.

We would grow quiet and, though we didn’t want to admit it at first, we found ourselves sad when our daily read-aloud would come to an end. Years later when I would read from that book to my children, I would hear his deep slow Eeyore voice as I would read, “Give Rabbit time and he’ll always get the answer.” So often, I recall his reminder that most kids are like Rabbit; they simply need more time.

Ed and Jo Anne gave Brad and me a serving tray for our wedding. The card said, “Serve one another and the years will fly by.” They were right. Jo Anne gave me sourdough starter which I nurtured for years and cried when the final loaf of what descended from her own starter was gone. They happily shared their 50-yard-line faculty UT/OU football tickets with Brad and me, they visited us in Houston, and we would visit them in Austin, and eventually Ed served on my dissertation committee. When we had our first child, they sent us a copy of The House at Pooh Corner with the reminder to read aloud to her each and every day. Many years into my career when a trusted colleague where I was teaching hurt me deeply with unkind, actually cruel, remarks, Ed was the person I called first. I don’t remember exactly what he said, but I do remember ending the call knowing that, yes, everything would be ok. And it was.

I see the lessons I learned from Dr. Farrell in the best teachers across this nation. Daily I see these teachers worrying about the “why” of the lessons they are told to teach. I see you offering your students who could be named Rabbit a bit more time, reminding these children they will get it. I watch you sometimes ignore your own needs as you serve others. And I see you give books to kids so that they might get lost in the story and perhaps, along the way, find themselves.

Perhaps the most important lesson Ed offered is the value of a literate life. He thought the deep and wide reading of literature would help us become moral humans. In one of his most-quoted articles, “Listen, My Children, and You Shall Read” (English Journal 55, no. 1, Jan. 1968), he wrote:

In short, though the bridges into literature are many and varied, one must be built for nearly every selection to be taught. When I am unsure about how to build, I inevitably fall back on the one constant we have, the emotional experiences of the youngsters. No matter the class, the students will have had some experience with hate, with fear, with loneliness; some bent, albeit warped at times, toward honor, toward courage, toward love. Intellectual traditions change from century to century, decade to decade, and with the explosion of knowledge in our time, often from year to year. There nevertheless remains a continuity in human experience, a continuity provided in the heritage of all men: we are born, we feel, and we die. And though we die, our literature remains behind, reminding those who follow what it was, and is, to be human.

“Our literature remains behind.” Ed meant that body of work we read, study, and embrace. But if you would allow me to let the literature he left behind to be the many lessons he taught, then you will perhaps forgive my revision of his words: His lessons remain, reminding those who follow what it was, and is, to be a good teacher. I know your heaven is filled with books, Dr. Farrell. I hear laughter from those heavenly clouds as strangers discover your quick wit, and I know that for an hour, each afternoon, as you open a book to read aloud, all those who are near quiet to hear your words as you say to them all, “Let’s begin.”

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.